THE ORIGIN OF THE BIDLAKE PRIZE

What

lies behind this roll of honour of great British cyclists? Who was Bidlake, and

what was the origin of the prize? Strangely enough, the history of the Bidlake

prize began with a death. In July 1933 an elderly, well-dressed,

scholarly-looking man was returning to his home in North London from a day’s

cycling in his favourite countryside in Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire, when,

descending Barnet Hill, a car suddenly turned across his path directly in front

of him. The crash was inevitable, but the cyclist did not appear to be too

seriously injured, although his machine was wrecked. He was able to make his way

home unaided, but some time later he seems to have suffered some form of delayed

shock, and he collapsed. His condition worsened, physically and mentally, and

exactly three weeks after the crash, he died.

What

lies behind this roll of honour of great British cyclists? Who was Bidlake, and

what was the origin of the prize? Strangely enough, the history of the Bidlake

prize began with a death. In July 1933 an elderly, well-dressed,

scholarly-looking man was returning to his home in North London from a day’s

cycling in his favourite countryside in Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire, when,

descending Barnet Hill, a car suddenly turned across his path directly in front

of him. The crash was inevitable, but the cyclist did not appear to be too

seriously injured, although his machine was wrecked. He was able to make his way

home unaided, but some time later he seems to have suffered some form of delayed

shock, and he collapsed. His condition worsened, physically and mentally, and

exactly three weeks after the crash, he died.

The man in question was Frederick Thomas Bidlake, and

it is probably true to say that he was the best-known figure in British cycling.

He was no longer a star rider, although he had been a record-holder on three

wheels back in the 1890s; but he later turned his energies to the administration

of the sport, with outstanding success. He was President of the North Road CC,

and of the Road Records Association, and Chairman of the Road Racing Council,

the body set up in 1922 to guide the sport of time-trialling, and which later

became the RTTC, now Cycling Time Trials. He was a skilled timekeeper, and his

knowledge of all matters legal, historical and technical connected with cycling

and cycle-racing was unrivalled. He was also a writer who had published several

books and contributed to magazines including “Cycling” from the year it was

launched in 1891 until the very eve of his death. But his most outstanding

achievement had occurred almost forty years earlier, when he rescued road-racing

in England from the disorder into which it had fallen, and virtually created the

sport of time-trialling.

In 1933 Bidlake was 66 years old, and in the months

before that tragic accident he had been preparing to retire from all his

official positions and move from London to Devon. He was held in such high

esteem that a scheme was in progress to present him with a special and award and

a cheque in recognition of his services to cycling. When the news of his death

broke, the cycling world was deeply shocked, and this tribute was immediately

altered to become a memorial for Bidlake. This took two forms: first a small

memorial garden was laid out beside the Great North Road at Sandy in

Bedfordshire; and second, an award was set up, to be given each year for

outstanding achievement in cycling, or for outstanding services to the sport.

The whole enterprise was funded by public subscription. The first award was made

in 1934, when the garden was officially opened in September of that year, a

crowd estimated at 4000 gathered to see it, cyclists who had come from all over

England to honour Bidlake’s name. Had Bidlake not died when he did, he would

presumably have received his cheque and his memento – perhaps a silver plate or

a statuette or something of that kind – and there would have been no Bidlake

Prize.

What

Bidlake had achieved for bicycle racing in the 1890s deserves to be explained

more fully, since it largely determined the course of cycle sport in England for

the next half century and more. Early road racing in the 1870s, 80s and 90s was

a very rough and ready affair, with no set rules, in which the contestants used

pacers to help them, so that a field of a dozen racing men, each with two of

three pacers, could end up as a bunch of thirty or more passing through towns,

villages and countryside at what seemed then like a high speed. The motor car

had not arrived of course, so the only other road users were pedestrians and

horsemen, and the latter developed great hostility towards cyclists, and used

their influence to discourage cycling generally and to prevent racing in

particular, which was then referred to as “furious riding,” and condemned as

socially irresponsible. There were never any laws passed to outlaw or limit the

right of cyclists to use the roads, but local constabularies had the power to

stop cyclists and prosecute and fine them for obstructing the highway. In areas

where cyclists congregated and where races were held, such as Bidlake’s country

along the Great North Road, a form of guerrilla warfare developed, as racers

shifted their venues and dodged the police who were sent out to stop them.

What

Bidlake had achieved for bicycle racing in the 1890s deserves to be explained

more fully, since it largely determined the course of cycle sport in England for

the next half century and more. Early road racing in the 1870s, 80s and 90s was

a very rough and ready affair, with no set rules, in which the contestants used

pacers to help them, so that a field of a dozen racing men, each with two of

three pacers, could end up as a bunch of thirty or more passing through towns,

villages and countryside at what seemed then like a high speed. The motor car

had not arrived of course, so the only other road users were pedestrians and

horsemen, and the latter developed great hostility towards cyclists, and used

their influence to discourage cycling generally and to prevent racing in

particular, which was then referred to as “furious riding,” and condemned as

socially irresponsible. There were never any laws passed to outlaw or limit the

right of cyclists to use the roads, but local constabularies had the power to

stop cyclists and prosecute and fine them for obstructing the highway. In areas

where cyclists congregated and where races were held, such as Bidlake’s country

along the Great North Road, a form of guerrilla warfare developed, as racers

shifted their venues and dodged the police who were sent out to stop them.

Bidlake

himself and all enthusiasts of road racing were deeply concerned about this

situation, but given the public hostility against road-racing, no solution

seemed available. However there came a dramatic incident which made it essential

that an answer be found to this problem. In July 1894 a bunch of North Roaders

including Bidlake himself were taking part in their 50-mile race. A trap driven

by a woman approached them from the opposite direction, and seeing the cyclists

she became alarmed and tried to pull up the horse. Unfortunately she completely

mishandled the reins, with the result that horse and trap ploughed into the

cyclists, scattering them onto the roadway, injuring them and damaging their

machines. Neither the driver nor the horse were hurt, but the woman complained

bitterly to the chief constable of Huntingdonshire, who immediately banned

absolutely all bicycle racing in the county. Bidlake went to see the chief

constable to give the cyclists’ version of events, but the man was adamant that

their furious riding was to blame, and refused to rescind his decision.

Bidlake

himself and all enthusiasts of road racing were deeply concerned about this

situation, but given the public hostility against road-racing, no solution

seemed available. However there came a dramatic incident which made it essential

that an answer be found to this problem. In July 1894 a bunch of North Roaders

including Bidlake himself were taking part in their 50-mile race. A trap driven

by a woman approached them from the opposite direction, and seeing the cyclists

she became alarmed and tried to pull up the horse. Unfortunately she completely

mishandled the reins, with the result that horse and trap ploughed into the

cyclists, scattering them onto the roadway, injuring them and damaging their

machines. Neither the driver nor the horse were hurt, but the woman complained

bitterly to the chief constable of Huntingdonshire, who immediately banned

absolutely all bicycle racing in the county. Bidlake went to see the chief

constable to give the cyclists’ version of events, but the man was adamant that

their furious riding was to blame, and refused to rescind his decision.

Bidlake

saw that if other constabularies followed this lead, the whole future of racing

on the road was in danger of extinction. In this emergency he set himself to

analyse the problem and come up with a solution, and that solution was the

time-trial. These races, disorderly as they seem to us, were always timed, and

the riders were sent off in small handicapped groups, and the idea was that they

should come together to contest the finish. Bidlake’s big idea was to base the

entire race on time, but to keep the riders apart by sending them off at

intervals. The whole race should be a solo effort, the pacers were to be banned,

and the rider with the fastest time would be the winner. Moreover, Bidlake had a

legal turn of mind – as a young man he had wished to train as a lawyer – and he

saw that this was a race that was legally invisible: it could never be proved

that these men were racing against each other; it was merely a succession of

individuals riding along a road, and therefore it would avoid the charge of

“furious riding”, and the opposition to cycle-racing would melt away, which is

exactly what did happen.

Bidlake

saw that if other constabularies followed this lead, the whole future of racing

on the road was in danger of extinction. In this emergency he set himself to

analyse the problem and come up with a solution, and that solution was the

time-trial. These races, disorderly as they seem to us, were always timed, and

the riders were sent off in small handicapped groups, and the idea was that they

should come together to contest the finish. Bidlake’s big idea was to base the

entire race on time, but to keep the riders apart by sending them off at

intervals. The whole race should be a solo effort, the pacers were to be banned,

and the rider with the fastest time would be the winner. Moreover, Bidlake had a

legal turn of mind – as a young man he had wished to train as a lawyer – and he

saw that this was a race that was legally invisible: it could never be proved

that these men were racing against each other; it was merely a succession of

individuals riding along a road, and therefore it would avoid the charge of

“furious riding”, and the opposition to cycle-racing would melt away, which is

exactly what did happen.

History was made in October 1895 when the North Road CC

promoted a race along these lines. There were 22 starters, but the weather

conditions were atrocious, with high winds and heavy rain, so that only six men

finished; the winner was Gordon Minns in a time of 2:56:26. A new era of road

racing had begun in Britain, but very few people were aware of the fact, and the

race was reported in just two sentences in the cycling press. Writing in

“Cycling” magazine a short while later, Bidlake explained his novel idea: “There

is just a chance that the limitation of fields, the barring of pacemakers, and

the provision of a sufficient interval between the men, may render racing of a

modified sort once more practical.” These few words may be regarded as the birth

certificate of time-trialling.

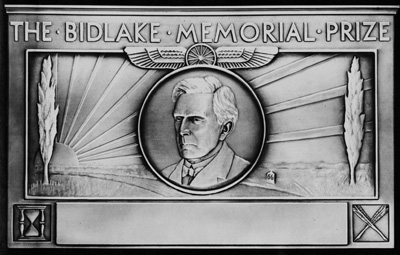

These new rules did not establish themselves overnight,

for there was no governing body for road racing to enforce them, and there was a

period of transition that lasted several years. Nevertheless more and more clubs

began to promote their races as individual time-trials, races that had been run

on the track returned to the road, and within ten years of that first North Road

50, the time-trial had become the normal form of road racing. This was Bidlake’s

unique legacy to the sport of cycling in England, and Bidlake watched and guided

its development over the following 38 years until his death. The Bidlake Plaque

itself was carefully designed to incorporate symbols of the sport and of his

life. His portrait is framed by the rising sun, the poplar trees on Great North

Road, the hour-glass representing time and the quill pens representing his

career as a writer; the 66 milestone shows the age at which Bidlake died.

Few men can have claimed to have invented a national

sport single-handedly, as Bidlake did, but he never lost his passion for all

aspects of cycling, and the roll of honour of those who have won the prize

serves to link the Bidlake name with the entire history of the sport in this

country for three generations. Bidlake himself would surely have been greatly

surprised at this, but greatly delighted too.

The

Bidlake Memorial Garden